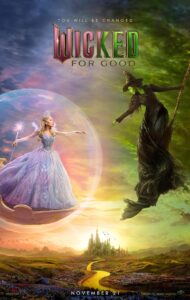

Wicked – For Good

Construction of the yellow brick road leading to the Emerald City is proceeding apace, and only one danger seems to threaten the peace in the land of Oz: the Wicked Witch of the West. But things are different than they seem. The first part of the film tells us: Elphaba, the witch, is not wicked at all and, on the contrary, wants to tell her world the truth about the Wizard’s lies, but the propaganda concocted by Madame Mortimer has made her unpopular. Glinda, the good witch of the North, however, is the opposite: she has no powers, she is a witch only by virtue of a pretense, yet everyone loves her.

Wicked thus continues the epic story of the friendship between two young women seemingly as distant from each other as pink is from black, but in reality just waiting for the right moment to join forces and rewrite their version of history.

The second part of the epic, based on the musical by Stephen Schwartz and Winnie Holzman (and in turn based on Gregory Maguire’s bestseller), unfolds along two distinct lines: on the one hand, the political allegory, which reiterates and elaborates on the themes of the first part; on the other, the unfolding romance between the outcast Elphaba and Prince Fiyero.

On the first front, almost as if to distance itself from accusations of vacuity and illusionism, Jon M. Chu’s film delves into the witch-hunt atmosphere (literally) and the description of how the newspapers and magazines relentlessly churned out by Madame Mortimer construct and sustain the image of a wonderful Oz (Wonderful is one of the best issues of this chapter), despite it being a brilliant “fake.” Even faced with his unmasking, the script says, the subjects of Oz would not stop believing him, because in today’s world, what is true is what is believed, not what can be proven. Not the facts, in short, but the confirmation of one’s opinion, no matter how far from reality.

This is also the line of reasoning that Elphaba offers Glinda for the reason for her condemnation: he is the scapegoat the people need (“They need someone to be wicked so that you can be good”). And finally, this reshuffling of roles also includes the imaginary origin stories of the Lion, the Tin Man, and the Scarecrow, as well as the reasons and dynamics of the Wicked Witch of the East’s death and the cyclone that transported Dorothy from Kansas to the land of Oz.

There’s a lot of story to unravel in this second part of Wicked, and a certain tendency to take itself more seriously than necessary. But it also confirms the quality of the entertainment offered in the first half, as well as the presence of more or less memorable numbers (not all of them were equally successful, it must be said). Despite the scathing line (“For the first time I feel wicked”), delivered without a shred of irony, the romantic moment is one that works, and its reprise at the end allows the entire film to be read as a love story: something that didn’t even remotely exist in Baum or the MGM film, and which is instead a cornerstone of the fanfiction genre.

In the end, as expected, we return to the beginning, to the celebration of the Wicked Witch of the West’s death, but things are different from how they appeared almost five hours earlier, or at least now we see them “through different eyes.”