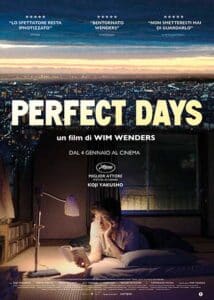

Perfect Days

Tokyo, today. Hirayama is a sixty-year-old Japanese man who cleans the city’s public toilets with meticulous attention to detail and painstaking dedication to his work. Every day he follows the same routine: careful personal cleaning before and after cleaning other people’s bathrooms, watering the plants that he saved from the city’s carelessness, a sandwich in the park at lunchtime. Along his route he sometimes stops to observe the plants above him, taking photos of the foliage, or has a snack at some diner. And every now and then he has some encounters: with Takashi, the boy who takes over the afternoon shift of cleaning the bathrooms, with a girl in the park, with a homeless man disconnected from reality, with the owner of a restaurant who gives him small preferential treatments. And when he gets in his van he listens to Lou Reed (with and without the Velvet Underground) and Patti Smith, The Animals and Van Morrison, Otis Redding and Nina Simone, just as when he is at home he reads William Faulkner and Patricia Highsmith, but also the “underrated” Aya Koda.

Perfect Days chronicles Hirayama’s “perfect days” as a quiet affirmation of everyday dignity.

The man carries out his work with precise and essential gestures, welcoming occasional human contact (even in the anonymous form of a game of tic-tac-toe proposed on a piece of paper) with generosity and respect. Everything about him has remained analogue, like the cassette tapes he listens to or the camera whose rolls of film have to be developed, and the photographs are collected in numbered boxes that archive the nostalgia of time that passes.

Wim Wenders, as director and screenwriter (with Takuma Takasaki), takes advantage of his great familiarity with documentaries to create a fiction film that follows the days of its protagonist like a hidden camera, and then tells the dreams of Hirayama as an artistic elaboration of the day just experienced.

Wenders’ architectural conception embeds the human figure in well-squared and bordering spaces (starting from the 4:3 format which at a certain point becomes the even narrower one of the cell phone shot), and in a Tokyo where the sun rises ( it is no coincidence that we are in the Land of the Rising Sun”) accompanied by the perfect song (The House of the Rising Sun). Franz Lustig’s clear and precise photography accompanies the portrait of the serene and composed solitude of a man who knows he belongs to a another era and who has made peace with his past mistakes.

Koji Yakuso, who some will remember in Babel by Alejandro Inarritu but also in The Third Murder by Hirokazu Kore’eda or The Eel by Imamura Shohei, is the extraordinary interpreter of this almost silent film which unfolds in purity through a contemplative but never artificial gaze .