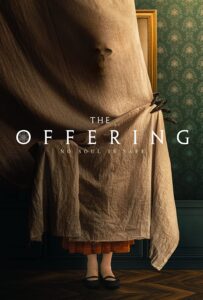

The Offering

Elder Yosille, deeply disturbed by the disappearance of his wife, deepens his esoteric knowledge and tries to summon a spirit to bring his wife back to life. But something goes wrong and Yosille kills himself with a dagger to try to avoid worse trouble. Arthur, accompanied by his pregnant wife Claire, returns to the family home to find his elderly father Saul and rekindle relations, closed in a turbulent way.

Saul is happy to see his son again and also welcomes his daughter-in-law warmly. Heimish, a collaborator of Saul (who runs a funeral home in the house), is more suspicious of Arthur’s real intentions. When he discovers that Arthur is in dire financial straits and has come mainly to induce his father to put his house as collateral for a loan, Heimish reveals this to Saul, deeply upsetting him. But there’s something worse: in the funeral home of the house there is the body of Yosille and the evil spirit that he has evoked has not abandoned him.

Gloomy and obscure, immersed in the dense moods of tradition and in the darkness of very ancient demons, the film finds its main strength in the suggestive setting within the Jewish community, which provides an important support of originality and credibility, as already in the recent The Vigil .

The long preparatory and descriptive phase that takes us into the particular environment – the family home, in essence – in which the protagonist returns accompanied by a non-Jewish wife (and therefore essentially a stranger, but not hostile or opposed) is conducted with attention and care for details and for the deepening of psychology and characters. The conflicting relationship between Arthur and his father is described without abuse of clichés, but with a good balance that credibly distributes wrongs and reasons and manifests the good intentions of each, undermined however by Arthur’s reticence to reveal his real situation to the public. father.

The second part of the film, in which the consequences of the premises develop in a more dynamic way and space is given to the otherworldly manifestations of the evil spirit, is perhaps more ordinary, staging, albeit always with an appreciable and even spectacular dignity, the usual paraphernalia of that kind of horror that makes haunted houses, ferocious spirits and possessions its main subject. In some cases the disquieting climate is well rendered – as in the mirror scene, with the immobile figures in “reality” and normally animated in their reflection in the mirror – in other cases the imaginary knows more than has already been seen and the evil creature, used however in a wisely sparing way, it partially betrays a certain lack of inventiveness and budget.